The drugs we used on their own

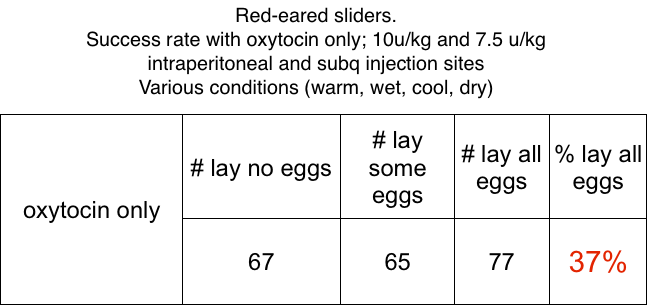

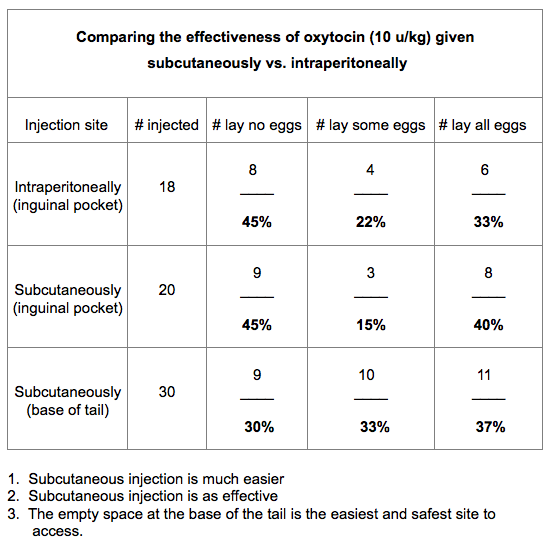

The table above shows how poor the results were using oxytocin alone (Remember that “success” for us means that the turtle laid all its eggs after one injection). We pooled the intraperitoneal and subq results because they were essentially identical as the table below shows.

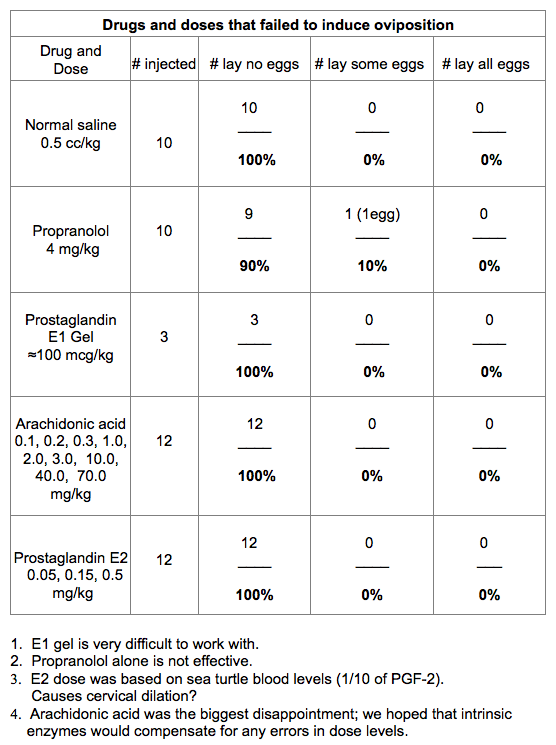

Because of these poor results with oxytocin, a success rate of better than 40% became our target when we experimented with other agents. The table below shows a number of agents that we had no success with on their own. We used normal saline as a control and, of course, it had no effect.

One striking failure was arachidonic acid, the precursor to the prostaglandins. It is known to induce oviposition in birds (Wechsung and Houvenaghel 1981), and lizards (Guillette et al.1992). We tested a wide range of doses. Since arachidonic acid is the precursor for many prostaglandins we thought it might be rapidly metabolized to the prostaglandins involved in oviposition. Unfortunately we were wrong; it had no effect.

A gel made with misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) by crushing Cytotec tablets and suspending it in a gel was introduced into the cloaca with a 20 ml syringe and soft plastic tube. This is similar to the technique used to induce childbirth in humans where the gel is applied intravaginally (Frank and Huffaker 1995). However the turtles resented the method and spread the gel all around the lab as they expelled it, rendering it dangerous because prostaglandins are readily absorbed through the skin and mucous membranes of humans so they need to be handled with care. The three turtles we managed to load with the gel failed to respond.

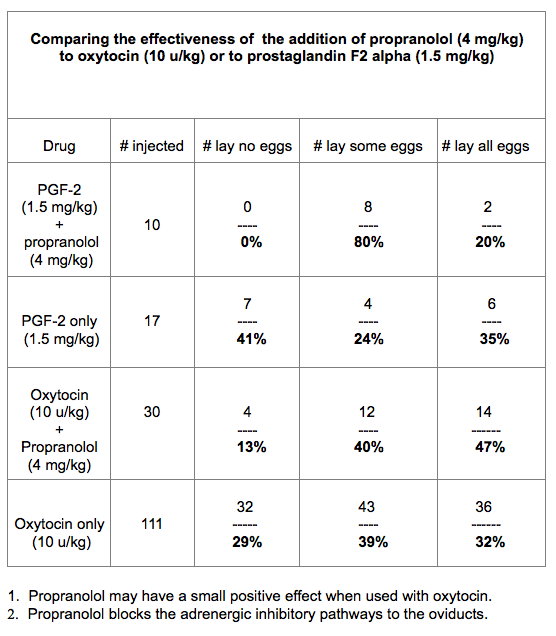

Propranolol, a beta-blocker used to reduce the peripheral manifestations of anxiety, did not work on its own but seemed to have a minimal effect when combined with intraperitoneal oxytocin as you can see in the table below.

In later experiments with spiny softshell turtles (Apolone spinifera) propranolol seemed to have a positive effect when combined with other agents. You can see this data in the chapter of the “Primary data” section titled “The drugs we tested on SSS.”

Surprisingly, prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2), an agent known to be involved in oviposition in sea turtles (Guillette et al. 1991a), also proved ineffective on its own. As shown below it also did not enhance other agents very much, was expensive to purchase, and time consuming to prepare, so we stopped experimenting with it.

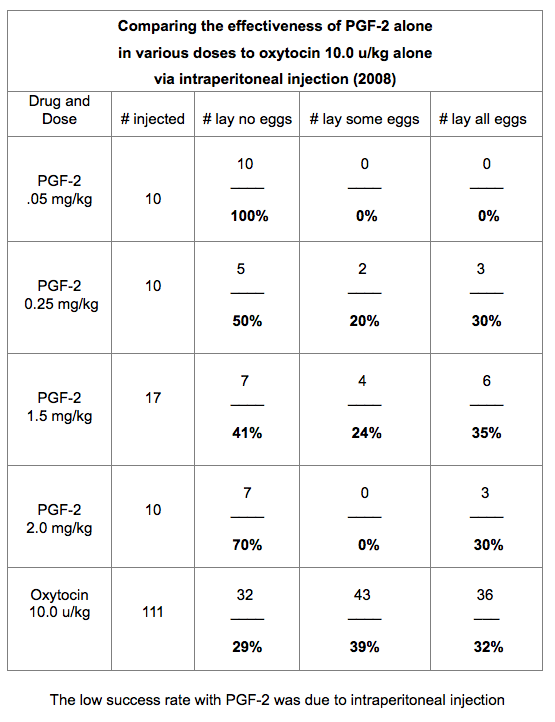

While we were still using intraperitoneal injections we decided to experiment with Lutalyse (PGF-2). This is an agent that has been found to be critical in the cascade of events leading to childbirth in humans and egg laying in birds (see the “2007 article” on this web-site for details). We had high hopes that it would prove effective. As you can see in the table below, it didn’t seem to be the case. Lutalyse seemed to be no more effective than oxytocin. This was a big mistake! We had administered the Lutalyse into the peritoneum which had a huge surface area. This caused the agent to be metabolized so quickly that it did not reach adequate blood levels to have an effect.

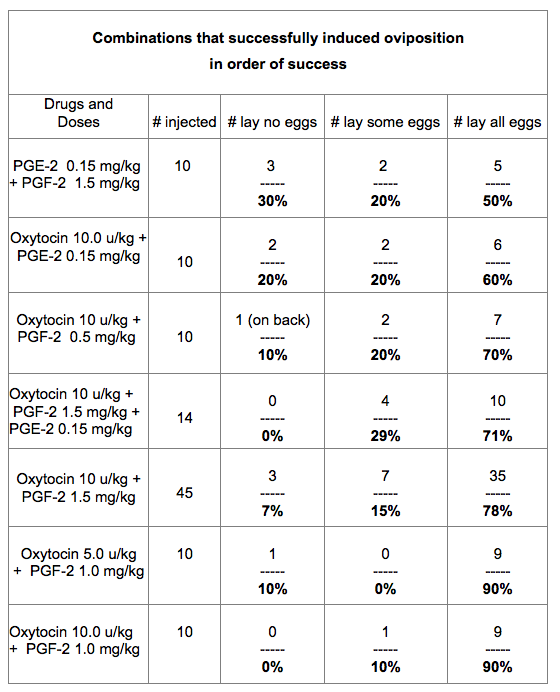

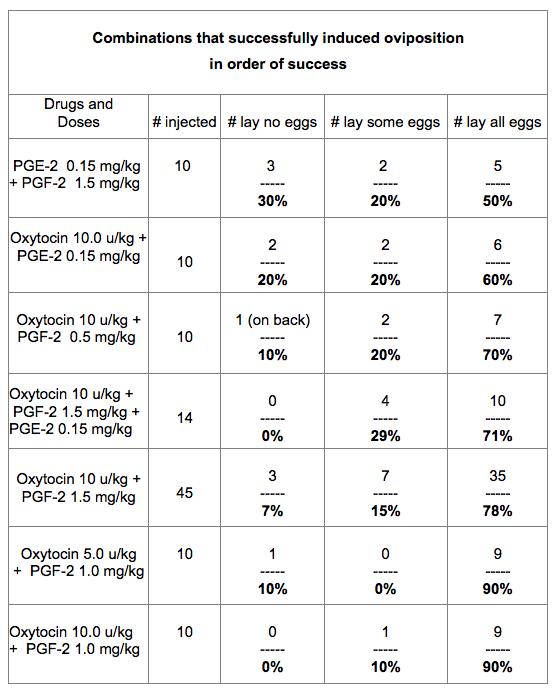

We then made the mistake of assuming that Lutalyse was not an effective agent on its own and began to experiment with a variety of agents combined with oxytocin. From that point on all injections were given by the subq route at the base of the tail. The table below shows our results.

The dramatic improvement in success when we combined oxytocin and Lutalyse (PGF-2) led us down a primrose path that consumed several years of work as we tried to determine the most effective doses and sequences of injection for those combined agents. In fact, the success rate increased because of the subq injection technique, not the drug combination. It took several seasons to realize that Lutalyse alone was more effective than when it was combined with oxytocin!