The background of our research

During a visit to John Legler’s lab in 1977 we met a young graduate student named Jim Berry. I explained to Jim that we liked to keep hatchling turtles for a year or so, release them, and then replace them with new hatchlings. When I complained about how difficult it was to catch the hatchlings he suggested I learn how to “make them.” Jim then showed me how they had been experimenting with injecting oxytocin intraperitoneally to induce turtles to lay their eggs (Ewert and Legler 1978). I didn’t realize it then, but that simple lesson was to change our lives.

From 1978 to 2005 we tried to induce about 250 turtles (see web-site section labeled “2007 article”). Our first obstacle was to find the gravid turtles. I made it a habit to take my vacation time in June and we would go out most evenings and mornings to collect turtles that were looking for a nesting site in our area of Pennsylvania, USA. We sought aquatic turtles that were emerging from the water to lay their eggs and eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina) which we found in known nesting areas.

All the turtles were palpated and had to have firmly shelled eggs before we would induce them. It became clear from the very beginning that oxytocin did not always work. Some species like spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) responded pretty well; laying all their eggs 82% of the time. Other species like wood turtles (Clemmys insculpta) and snappers (Chelydra serpentina serpentina) almost never laid all their eggs.

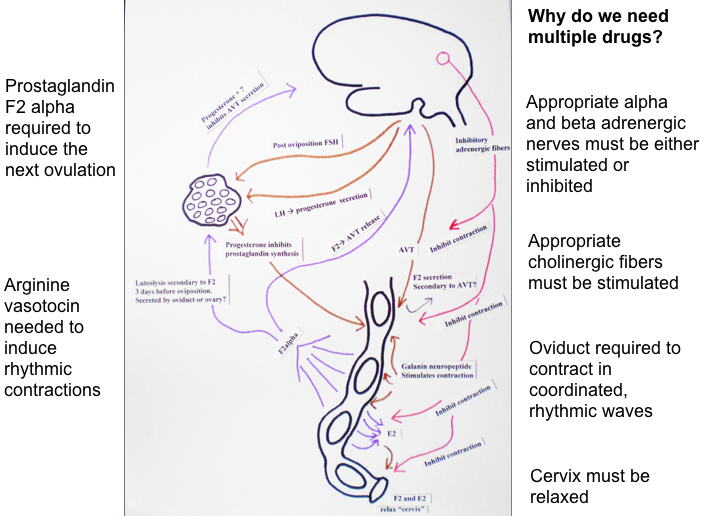

We were able to prove that eggs obtained by induction were as viable as natural nest eggs (also see Wilgenbusch 2000) and that oxytocin, used alone, had only an inconsistent effect. By the early 1990s it had become obvious that using oxytocin alone was way too simplistic. It is a mammalian hormone and it’s unrealistic to expect it to substitute for the complex interactions of steroid hormones, neurohypophysial peptides, prostaglandins and direct neural modulation that is necessary for coordinated oviposition (Guillette et al. 1990b). The illustration below summarizes some of the pathways involved.

In addition to an inconsistent affect, there were other problems with using oxytocin alone. One was false nesting; which occurs when the turtle re-emerges three days to two weeks after a successful induction, digs a nest hole and then just sits there because there are no eggs to be laid (Carr et al. 2008; Iverson and Smith 1993; McCosker 2002; Tucker et al. 1995) . This is not a major problem for a captive animal but it could easily prove fatal for a wild turtle.

The other problem was delayed ovulation. In turtles that multi-clutch, the gonadotropins (follicular stimulating hormone [FSH] and luteinizing hormone [LH]) are critical agents involved in the ovulation of the next clutch (Licht et al. 1979). It is known that prostaglandins have a role in gonadotropin induced ovulation in birds, fishes, mammals and lizards (Jones et al. 1990). It would be expected that the same mechanisms were active in turtles. This suggests a role for prostaglandins in the egg laying process of turtles that multi-clutch. Given the complexity of the process of oviposition and subsequent ovulation of the next clutch, it is no surprise that giving oxytocin alone often fails to induce complete oviposition and can inhibit the following ovulation.

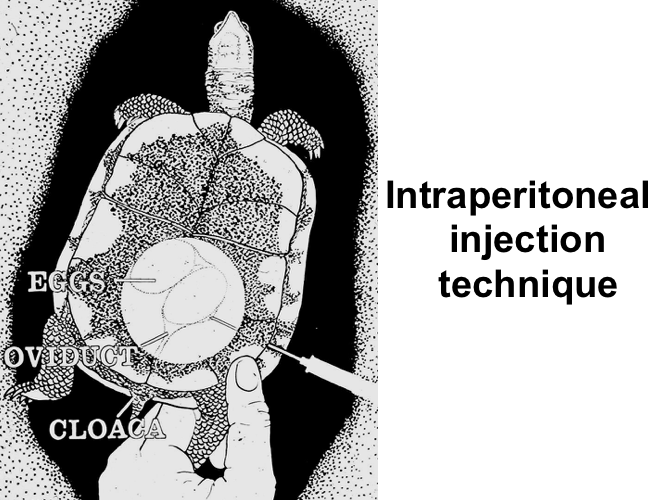

There were other difficulties as well. We didn’t know where the best place was to inject the oxytocin. Should it be given into the muscle (intramuscular), into the skin (intradermal), into the fat under the skin (subcutaneous) or into the peritoneal cavity (intraperitoneal) as Jim Berry had shown me?

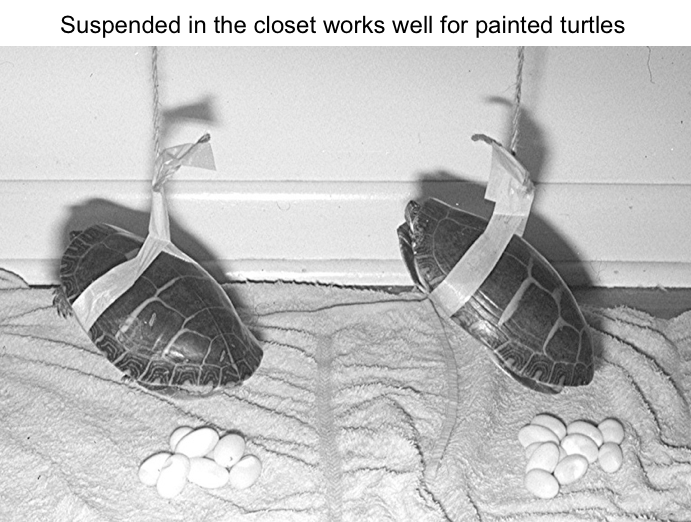

What should we do with the turtle after it was injected so there was the least anxiety for the animal? Hang it in a sling above some wet towels?

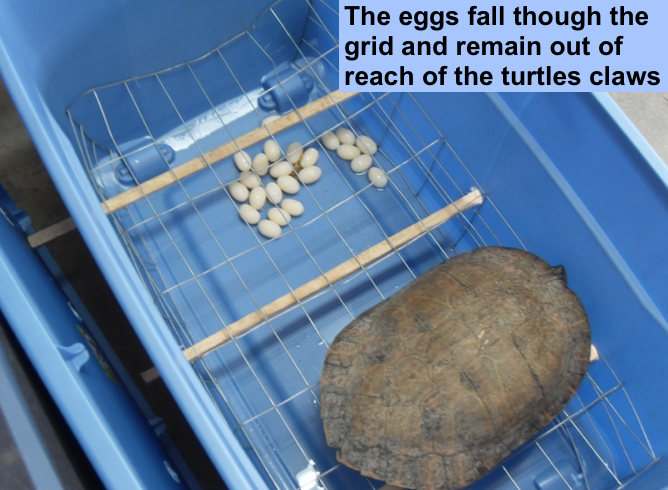

Should we place the turtle on a grid so the eggs would fall through onto a soft, moist surface?

Should we tape the turtle to the top of a post so it couldn’t move? Leave it in the water and watch it carefully so we recovered the eggs before they were torn apart by the claws on the hind legs?

Would it help to replace the oxytocin or add other drugs to the oxytocin to make the induction process more effective? Sedatives or beta blockers might eliminate the anxiety that inhibits induced egg laying. The prostaglandins that were normally released by hormonal action might need to be used with the oxytocin. Neurological agents (cholinergic, adrenergic and others) might be necessary to dilate the cervix, stimulate the oviduct or block natural inhibitory agents. Other hormones or hormone blockers like relaxin, estrogens or progesterone blockers might even be necessary.

All these possibilities would need to be tested in large numbers of animals, in some sort of controlled situation, to refine the induction technique but where were we going to get easy access to that many turtles?